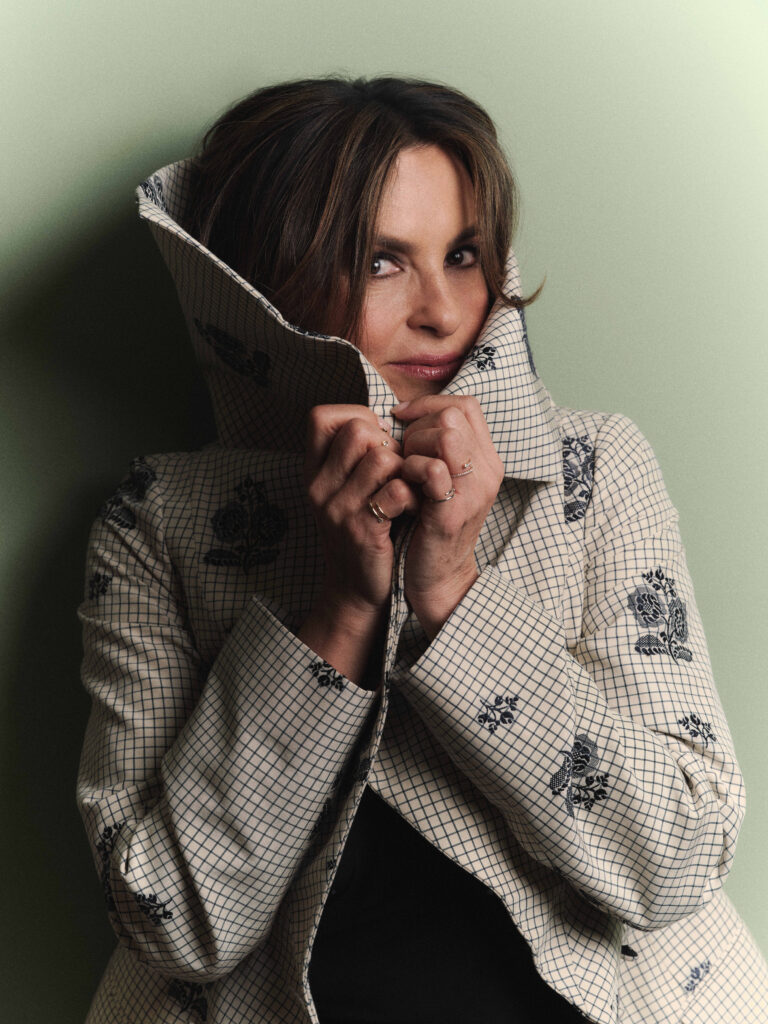

Mariska Hargitay: Power, Presence, and the Pursuit of Justice

Image by Rob Berry

About The Author

Corey Ruzicano

Corey Ruzicano is a writer and creative producer working at the intersection of arts, education, and social...

Not everyone gets a cat named after them by Taylor Swift. But Mariska Hargitay isn’t just anyone. As Olivia Benson, the no-nonsense detective on Law & Order: SVU, Hargitay became a household name and the face of one of television’s longest-running dramas. She’s used that power for good: through her work on-screen and off, she has become one of the most visible and vocal advocates in the fight against abuse. In 2004, Hargitay founded the Joyful Heart Foundation, an organization dedicated to transforming society’s response to sexual assault, domestic violence, and child abuse. Under her leadership, Joyful Heart has raised tens of millions of dollars, distributed 28 grants supporting frontline workers through the newly reimagined Heal the Healers Fund – a grantmaking initiative supporting professionals who work with survivors of abuse, and championed major legislative victories. In 2024 alone, 44 image-based abuse (non-consensual creation, sharing, or threat to share intimate images or videos) bills were passed across 30 states, and the Foundation’s flagship End the Backlog initiative helped pass nine rape kit reform bills in eight states. The organization also played a key role in efforts to extend or eliminate statutes of limitations for sexual assault in seven states and improve access to victim compensation in five more. At a time when celebrity activism often feels fleeting or performative, Hargitay’s is rooted in decades of consistent, unflinching work. She has shown that visibility, when used with purpose and grace, can be a powerful force for change. Here, Hargitay discusses how her work has informed her advocacy.

Tell us about your experience of being a leader. What does good, evolved leadership look like–on set or at Joyful Heart?

I feel deeply. I hold my beliefs deeply. I stand firm in my convictions and believe in my vision for what should be possible. I’m very fortunate to have people around me who are on board with realizing that vision. I also know what I’m good at, and what I’m not good at. So you end up with a team of people, each with their area of expertise, gathered around a heart-driven person in pursuit of something. At Joyful Heart, I am a member of the team whose specialty is holding out a vision and driving things forward. As far as leadership on the set goes, the show has given me so much, so it wouldn’t be right to show up any other way than with my best, or as close as I can get to it, every day. It would be a disservice to all the people who show up the same way every day.

The leaders I’m most willing to follow are those who lead by example, so that’s how I try to do it. If it’s 1 am and you’re shooting exteriors in the rain in November, it’s easy to get real cranky real fast. But if you do, and you’re the lead of a show, you’re inviting everyone to do the same. If you’re still cracking jokes with the rain dripping off the end of your nose, still smiling, still trying to do your best work, and supporting others in doing their best work, that sets a tone for everyone to follow. It’s deeply gratifying to see the effect that the tone I’ve been able to set has on the people I work with every day. It’s a mixture of work ethic, commitment, investment, deep gratitude, deep joy—and a lot of humor. And it’s always “Best Idea Wins.” I’m also always really proud when guest stars tell me that SVU is a special place to work.

What have you learned about yourself from being a mother?

My children have taught me how vital it is to be more present, mainly because the cost is high when you aren’t. I don’t mean present as in just being at home, I mean being present when I’m there. Kids are of course deeply attuned to whether or not you’re really there. My kids also confirm for me again and again how important humor is to survival on this planet. Our family would be lost without laughter. I mean that in the deepest sense. It has always been a realm of safety for me, and that has become true for all of us. Laughter is a shared language, it’s a connection at a deep and vitally important level.

I don’t think there’s any aspect of my life not affected by motherhood. In terms of my advocacy work, there was an intuitive deepening, multiplying, and expanding of the stakes. The same happened when it came to telling stories on SVU that involved children. The general idea that we’re trying to make a better world for our children becomes specific and personal as I experience my children encountering that world, both the changes my generation has been able to achieve and the pernicious underlying attitudes that have remained intractably the same.

You are the Founder and President of the Joyful Heart Foundation. How do you approach your advocacy work?

Most of the time we gain understanding in hindsight. I didn’t make an overarching decision when I started on SVU to make sexual assault my cause. As I’ve often said, I read the sexual assault statistics when I started on the show, and I just thought, “Why isn’t everyone talking about this?” The cause presented itself and said, “Pay attention to me.” Then came the letters from fans, and then came Joyful Heart, which was a large-scale response to the isolation and shame that so many survivors were telling me about. It was all forward movement into what I thought was needed. I of course don’t have the control experiment where I can see if I’d been on another show that focused on victims of another kind of crime, if I would have become an advocate for that cause. I’ll never know, but somehow I don’t think so. So many of the stories that survivors shared in their letters have stayed with me. One letter that has remained especially significant was from a woman who shared a story of disclosing to her mother that she’d been raped and that her mother didn’t believe her. The woman then said, “That was worse than the rape.” That statement underlines the trauma of not being believed and is an all-important reminder of the profound role that we can play when a survivor discloses their story to us.

“I feel deeply. I hold my beliefs deeply. I stand firm in my convictions and believe in my vision for what should be possible.”

Shop The Story

Have you had an experience that profoundly changed your mind?

I was involved in a serious motorcycle accident when I was thirty-four. [That] is how old my mother was when she died. The experience was deeply painful on every level. Something opened up for me after that. It was like I’d crossed a threshold. My trajectory was my own, my story was my own, without a predetermined ending. Within a year, I got the role of Olivia Benson on SVU. I can’t help but make a connection between that moment of liberation after the accident from what I feared was my fate and then stepping into this role that has become such a profound part of my life. It’s like I stepped out of a narrative that wasn’t mine and into my own story.

Is there a story you’d like to set straight?

Peter and I are currently in a disagreement about how to use a particular cabinet in our kitchen, and I think this magazine is the perfect place to hash that out. He’s wrong, he just doesn’t know it yet.

What have you learned about justice from your work on SVU?

One of my guiding statements on justice comes from Judith Herman in her book, Truth and Repair: “I propose that survivors of violence, who know in their bones the truths that many others would prefer not to know, can lead the way to a new understanding of justice. The first step is simply to ask survivors what would make things right—or as right as possible—for them. This sounds like such a reasonable thing to do, but in practice, it is hardly ever done. Listening, therefore, turns out to be a radical act.”

I find it extraordinary that after someone else’s will has been imposed on a victim of sexual assault, they are often pushed into a one-size-fits-all version of justice. The victim’s voice is negated in the act of violence, and then not heeded or even sought in the subsequent pursuit of justice.

I feel very proud that the longest-running show in TV history is fundamentally about the radical act of listening, bearing witness to suffering, and fighting for those who have been harmed. I think that is the core of what my character, Olivia Benson, gives to survivors.

What is the best thing about being your age?

I have more clarity.

How do you use your power?

I want my power to be a shared embrace of what’s possible. Real power is this glorious, beautiful, counterintuitive thing. The elegance comes in using your influence to create environments where everyone can be at their best.

I’ve also gained a lot of confidence through the process of navigating through my fear. I used to be much more afraid than I am now. I’ve been on the receiving end of the misuse of power. There was one time in my early twenties, I was shooting a scene for a movie and the director gave me a note to play it sexier. We did another take, and he still didn’t like what I was doing, so he called out to me from his chair, loud enough for everyone on the set to hear, “No no no. I said sexier. Like you want to fuck him. Haven’t you ever been fucked before?” I was shocked and deeply humiliated. After I walked away for a moment to gather myself, a couple of my co-stars came to check on me and offer support. Then I took a breath, went back, and tried to get through the scene. I’ve replayed that episode many times in my head and come up with many responses—Did you forget to take your meds this morning? Do you need to go home and learn to be a professional and come back tomorrow?—but one of my big takeaways all these years later is that the humiliation resides with him and not with me. He was of course fully entitled not to like what I was doing as an actor, but the fact that that’s the way he chose to communicate with me had everything to do with a need to exercise power—which is born of weakness—and a space where he could do so without consequence. I also learned a lot about how to be kind to myself afterward, that it’s normal to freeze in the moment, no matter how empowered a person I might be.

What’s an important lesson you’ve learned about being a good advocate for survivors?

My dad talked constantly about possibilities. He said that everything was within reach. And he always said the facts are the facts. He spoke the truth; he just called it the way he saw it. He laid the groundwork for me, and he started me on the road to feeling comfortable speaking my truth.

As far as listening to people speak their truths, the most important thing is just that: listen. I know what a gift it is when someone listens to me, really listens. It’s about being there and giving me time and space to talk. I know it’s healing for me when it happens.

Where do you turn when you feel lost?

I turn to my husband, Peter. I feel safe with him. He knows all the parts of me. And I think we take turns being lost and being the lighthouse.

What has Joyful Heart taught you about what is possible?

Many people and companies I approached when I was trying to raise funds, in the beginning, were dismissive of the idea or said that the optics of supporting an organization that focused on survivors of sexual violence weren’t favorable. I was given advice, likely well-meaning but narrow in its vision, to find another cause, to go where the money was, to focus on something with deliverable metrics for funders. Needless to say, I’m glad I didn’t follow the advice.

And it’s interesting, I sometimes get frustrated with myself, as I think many of us do, at my shrinking attention span in this age of so much new information coming at us all the time. But when I look at my life, it’s been this long exercise in paying sustained attention to vitally important things. I’m proud of that.

Has the feminism you fight for today changed from the feminism your mother’s world needed?

I look at the feminism of my mother’s time and feminism today, and I’m amazed at how different the terrain looks. And at the same time, so much of it looks the same. That isn’t because there haven’t been superhuman feminists doing extraordinary work, it’s because of the entrenched barriers to a world where women achieve parity and benefit from the same freedoms that men do. Of course, you can point to signs of progress. In 1960, women earned 60 cents for every dollar earned by men. Today that’s 82 cents. But it was 80 cents in 2002, so the curve has remained flat for the last twenty years. And when it comes to violence against women around the world, I’m as staggered today by the statistics as I was when I first encountered them.