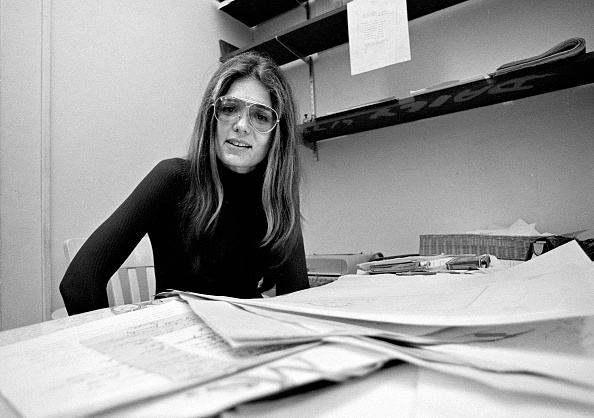

Gloria Steinem: The Heart of a Movement

At 91, the feminist icon is still planning her future.

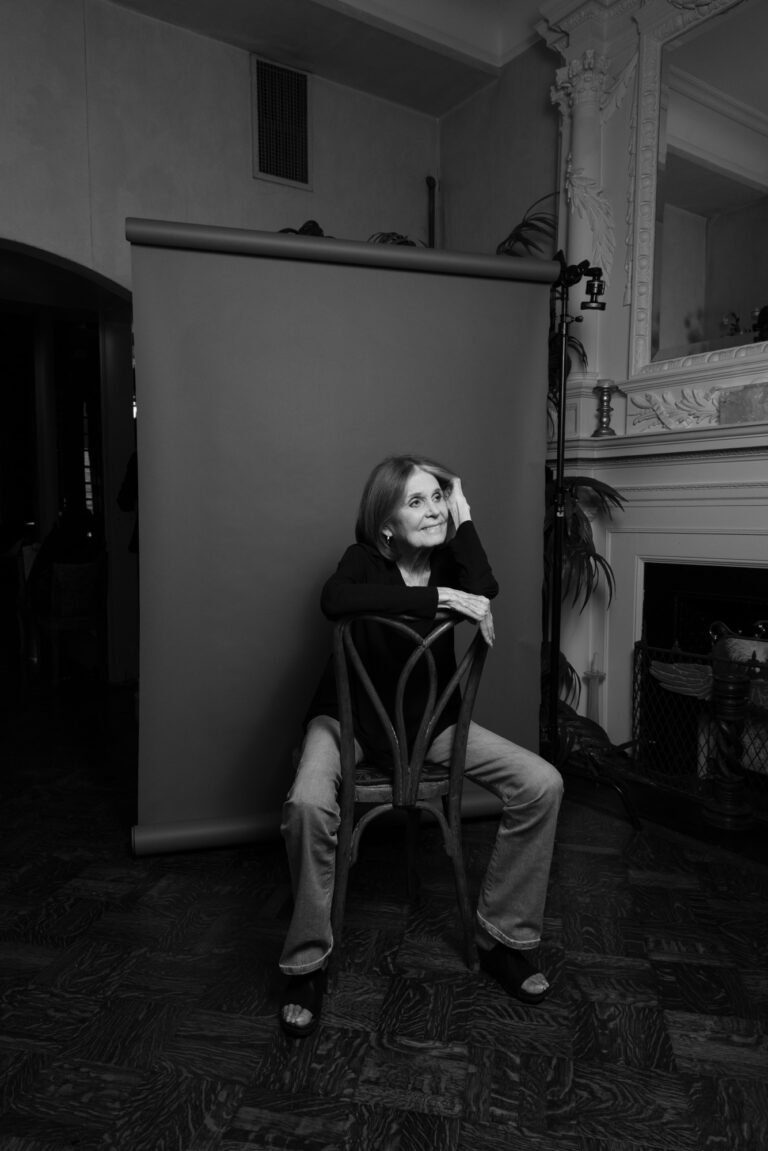

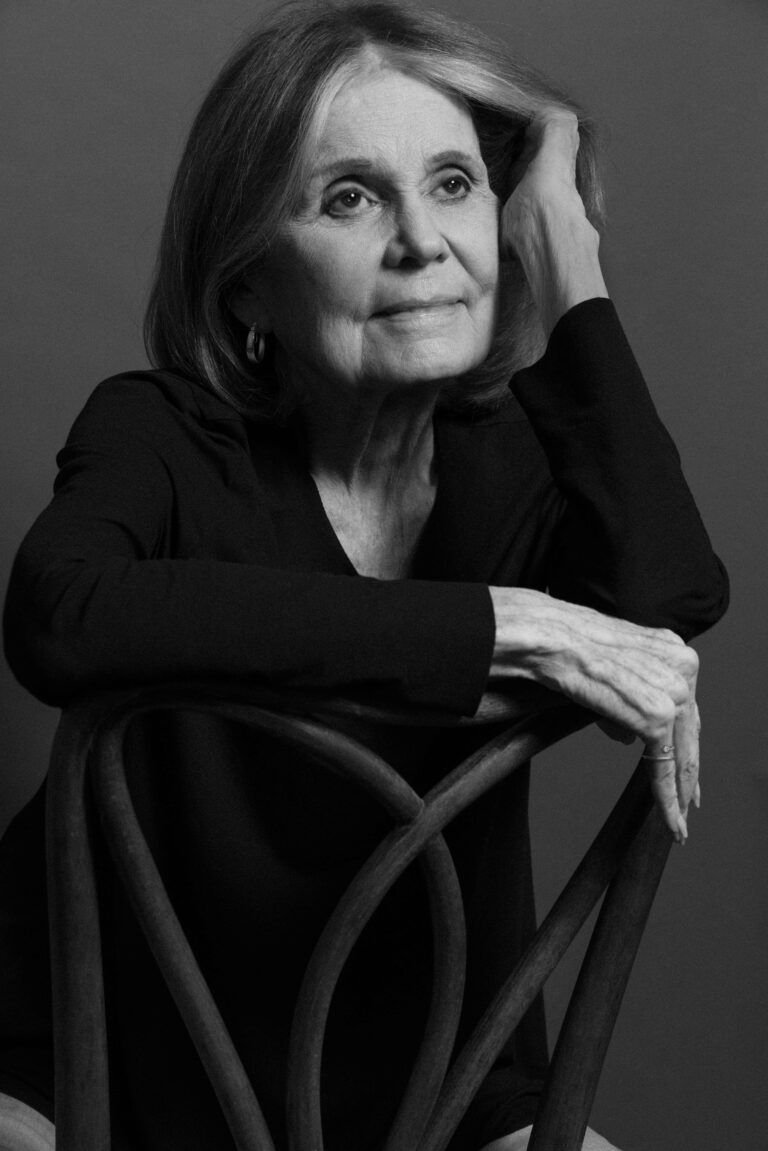

Image by Inez & Vinoodh

Image by Inez & Vinoodh

The Shift highlights women’s stories through the lens of impact. It hopes to contextualize history and inspire action.

Gloria Steinem has not been losing sleep over turning 91 this year. “I did go online and try to find the oldest woman in the world,” she grins. “I found a woman in the Himalayas who’s thought to be about 135. So I have a new goal, right?”

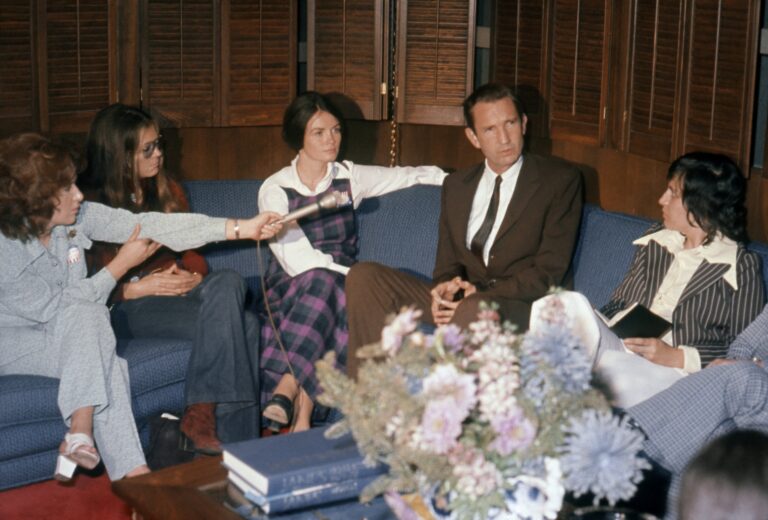

For decades, Steinem has been one of the most prominent figures of the feminist movement. Since her rise to fame in the 1970s, women in the U.S. have made significant strides—in workforce participation, higher education, and narrowing the wage gap, which improved from 57% to 83% of men’s earnings by 2023. Full gender equality, though, is still a distant goal. With hard-fought rights being rolled back across the country, it’s apparent that the issues Steinem brought attention to in the ’60s and ’70s are still relevant today. Despite this, Steinem remains a self-proclaimed “hope-a-holic,” often saying, “Hope is a form of planning.”

Steinem’s work has had a lasting impact. She co-founded institutions like Ms. Magazine and the National Women’s Political Caucus. Her work as a journalist helped shift cultural conversations around reproductive rights, workplace equality, and domestic labor—even coining terms like “reproductive freedom.” “We need to understand that our bodies are ours,” Steinem says during an interview at her Upper East Side home. “We get to make the decision.”

It’s a Thursday in September, and Steinem is getting ready for the cover shoot of The Shift, which will be photographed in her historic living room. Her home is a portal into her past: a kaleidoscope of deep red overstuffed chairs, yellow-striped wallpaper, and swirling, cloud-painted ceilings creates a space rich with wonder. Every surface holds the spoils of a life well traveled—tiny silver dishes, egg-shaped crystals, hand-carved wooden elephants from Kerala, Zimbabwe, and other corners of the globe. And books. So many books.

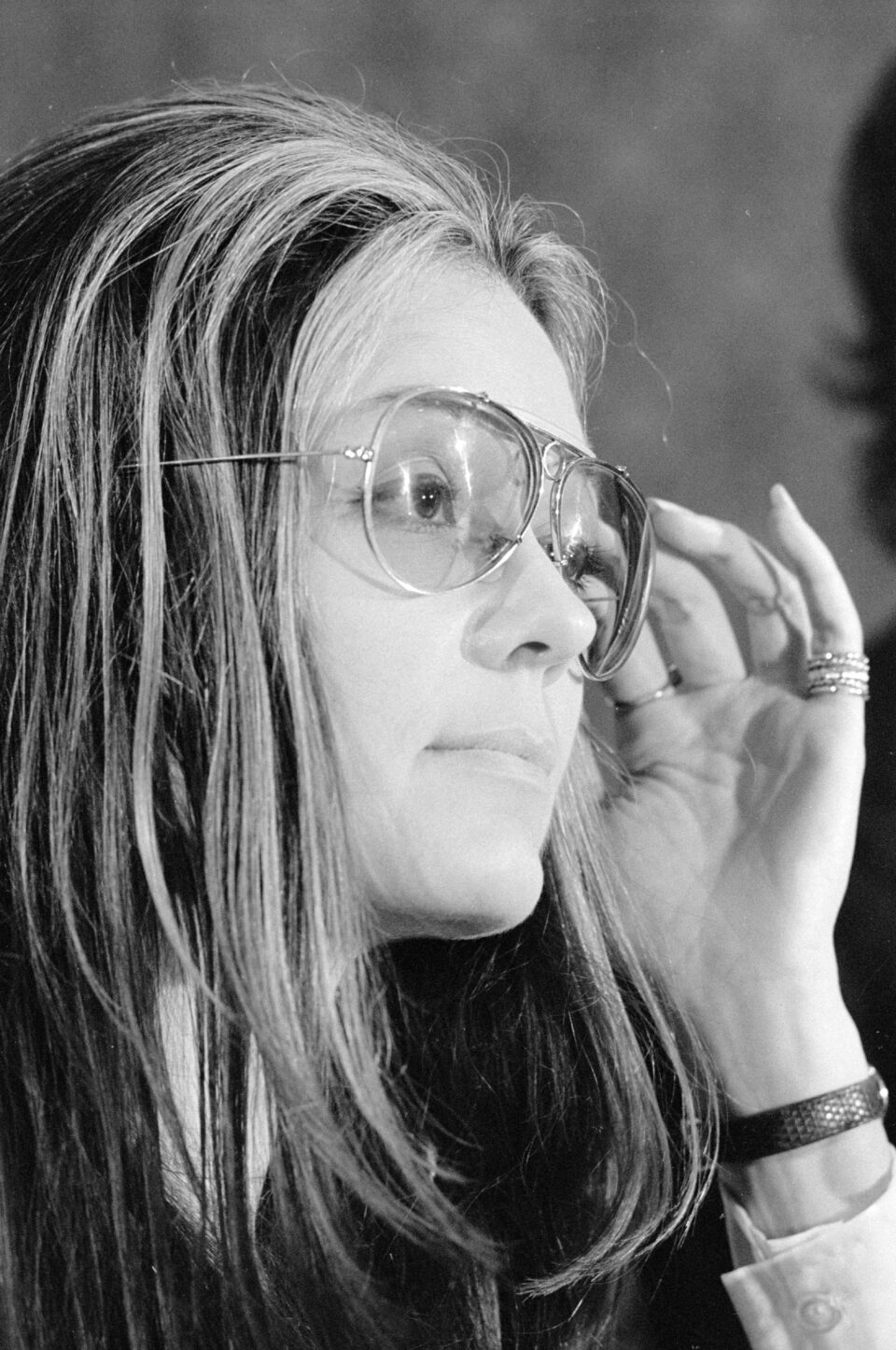

“Welcome home,” she calls from the bedroom. She’s wearing a black long-sleeve tee from Gap and her go-to Frame jeans—no makeup yet, as Daniel Martin, best known for creating Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle’s glowing royal wedding look, gently dusts her cheekbones with Tatcha’s Silk Canvas. On the bed beside her lie stacks of books—All About Love by bell hooks, Backlash by Susan Faludi, Well-Read Black Girl by Glory Edim, Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel—and several yellow legal pads holding notes for her latest collection of essays. And, of course, a pair of her trademark aviators are within arm’s reach.

Even in a room full of people, Steinem is unmistakably the center of attention. From across the room, stylist Sarah Slutsky holds two pairs of earrings from Michelle Obama’s Hoops To Vote collaboration: “Big hoops or small?” Steinem replies, “let’s do the big ones.” She is no stranger to a statement accessory, with a drawer solely dedicated to belts of all shapes and sizes. Today, her accoutrements also include a few Shiffon Co. Duet Pinky Rings that support female founders. Her hair has been freshly cut and colored, a regular ritual at the nearby salon of John D’Orazio, former hairdresser to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Finally, she picks out a pair of Italian chunky slide sandals and joins The Shift in her living room.

Steinem is exceedingly down-to-earth, witty, curious, and unwaveringly present. She gives each person in the room her full attention and she really listens to them, even if she’ll never see them again. When she speaks, lines you’ve already read or heard, land with unexpected clarity, honed over time into sharp, crystalline truths. Her deep understanding of people transforms the weight of her work into something joyful. “Laughter is a crucial emotion, it’s actually the only emotion that can’t be compelled,” she says. With one pointer finger in the air, she adds, “You can make people afraid. You can even make them feel they’re in love. But you can’t make them laugh if they don’t want to.”

Born in 1934 in Toledo, Ohio, Gloria’s childhood was semi-nomadic. Summers spent by a lake in Michigan were punctuated by her free-spirited father, Leo Steinem, packing up the family trailer and heading to Florida or California, dealing antiques along the way to finance the adventure. Her childhood education was informal and relatively structureless, shaped largely by books and an existence that was in constant motion. She didn’t attend school regularly until she was ten. “My father had two points of pride,” she says. “He never had a job, and he never wore a hat.” Then, pausing thoughtfully, “The truth is, I’ve never really had a job either.”

Her father encouraged her to be independent and curious. “He treated me like a person. Not like a child, but like my own person.” Her mother, Ruth Nuneviller, had been a newspaper reporter before Steinem was born, but after suffering a breakdown, spent periods in and out of sanatoriums. In Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, Steinem wrote of her mother’s decline, from energetic and book-loving to someone unable to hold a job or read. After her parents separated when she was ten, Steinem was thrust into the very adult job of being the sole caretaker for her mother while her older sister, Susanne, was away at college. “I was a tiny person caring for a grown person,” she recalls. “It probably required me to be more competent with less protection.” She dreamed about getting out of Toledo: “I’d tap-dance my way there if I had to.”

She did eventually find her way out. In 1953, Steinem enrolled at Smith College to study government, and in 1956, she received the Chester Bowles Fellowship to study in India. She took the leap—not only for the adventure it promised but also partly to avoid an engagement she couldn’t go through with. Though she remembers being afraid it would ultimately mean being alone forever, she picked up and moved to India for two years. It was there that Steinem was immersed in grassroots movements and Gandhian activism. “It helped me realize the importance of listening,” she says. “And of staying in community.” Exposure to different cultures and perspectives from her itinerant childhood and continued travel laid the foundation for her life as a journalist and activist.

After returning from India in 1958, she moved to New York and began working as a freelance writer. She spent the ‘60s writing on spec, carving out her voice in male-dominated newsrooms, and organizing with other activists. As she worked, she began to understand the necessity of becoming part of what was then called the Women’s Liberation Movement. At the time, suggesting that women were not only equal to men, but deserved the same kind of access to jobs, education, and pay, was a radical proclamation. In 1969, as a columnist at New York Magazine, she made a radical proclamation of her own: publicly supporting abortion rights by sharing her own story of getting an abortion at 22. “One of the most frequent ways abortion is restricted is by making it seem shameful,” she says. “Or something people don’t talk about.”

To Steinem, feminism is simple: “It just means the belief that females are equal human beings.” Yet, she adds, “That belief is still uncommon; otherwise, we wouldn’t need the word.”

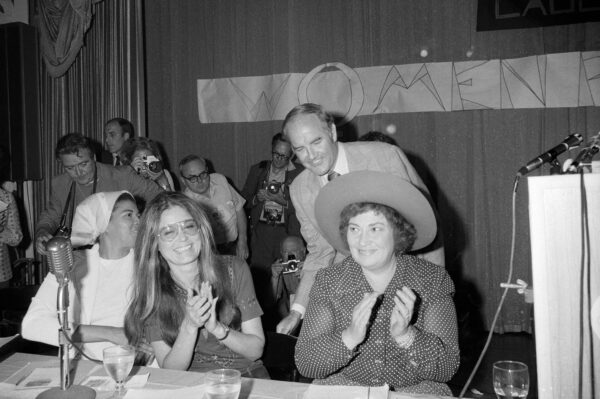

For someone who became a very public figure, it might be surprising that Steinem has a deep phobia of public speaking. She describes its symptoms in comic detail, “Each tooth seems to grow its own angora sweater.” But once she started speaking, she kept going, touring the country for years in the early ‘70s with close friend and fellow activist Dorothy Pitman Hughes to talk about the feminist movement at small community centers, church basements, and college campuses. “Dorothy was always more at ease on stage,” Steinem explains, “and she put me at ease.”

In 1972, she co-founded Ms. Magazine, which revolutionized women’s media by platforming female voices and focusing on women’s issues. With other feminists Patricia Carbine, Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Marlo Thomas, she established the Ms. Foundation to provide resources, support, and solutions to organizations led by women. During the ‘70s, alongside feminist organizers including Shirley Chisholm, Bella Abzug, and Betty Friedan, Steinem formed the National Women’s Political Caucus, which opened doors for women to run for office.

At 40, Steinem felt a personal shift. “I was in a generation where you were definitely supposed to get married and have children by a certain date,” she says. “40 was really the cut-off. So by the time I was 40 and still living my own life, that pressure began to dissipate. And at that point, it felt like I’d become who I really was.” She did, at 66, find a marriage of equals with environmentalist David Bale, father of actor Christian Bale.

“Many men are feminists. It’s a belief in equality that anyone can share.” Steinem explains. “We’ve all been in different stages of understanding, but if we approach each other with empathy, we can help expand each other’s realities.”

One of Steinem’s enduring lessons is that connection and joy can be found in the process of revolution. “People in the same room understand and empathize in a way that isn’t possible online,” she says. “Do we know our neighbors? Our coworkers? We can always call a gathering and see what we learn.”

To this day, in the same living room we’re sitting in now, Steinem still holds talking circles. They are exactly what they sound like: people coming together in a circle to speak honestly, to listen deeply, and to be present with one another. There’s no hierarchy, no pressure to perform, just the shared belief that everyone’s story matters. These circles create space for connection, healing, and sometimes even transformation. “If you can’t find the joy? The togetherness?” she asks, throwing up her arms, as if to say: what else is there?

Since moving into her Upper East Side apartment in 1968, Steinem has held countless talking circles, and today her brownstone serves as home to Gloria’s Foundation, with talking circles as a cornerstone of their programming. The foundation is committed to advancing the women’s movement through intentional dialogue, mentorship, and intergenerational coalition-building. In 2024, Gloria’s Foundation started a fellowship program, where participants have worked across categories like disability justice, feminist literature, climate activism, and art.

As the world evolves, so does Steinem. Her words continue to resonate with women around the world—through her books, speeches, and presence on platforms like Instagram and Substack. In helping women view their experiences as part of a broader system, she reminds us of the interconnectivity revealed through sharing stories. When asked what’s bringing her joy these days, Steinem smiles: “My friends, of course. Reading, watching Dance Moms.” She muses, “We experience laughter in all these same ways, [it’s] the most free emotion.”